It was the enchanting Mr. K, my birth-year cohort, who had the great idea, in the weeks before his (50th) Doomsday, to find and post the books of 1964. He gathered a fantastic list of titles, including lots of poetry and some fiction (in English and Spanish): Robert Duncan, Roots and Branches; James Wright, The Branch Will Not Break (a branch theme?); Elizabeth Bishop, Questions of Travel; Denise Levertov, O Taste and See; Ernesto Cardenal, Salmos; Nicolás Guillén, Tengo; Jorge Luis Borges, El otro, el mismo; and more. The list came with quotes and commentary, and occasionally spilled over into “1964-adjacent” books, other forms of print culture (most notably a very cool series of Time covers), and the Beatles album de rigueur (but one released in Argentina!). Superduper fun literary time capsule! I instantly became his most ardent fan–even started looking up works I didn’t know. And then Mr. K stopped.

I carried on merrily with my summer, happy in the knowledge that, while Mr. K had already crossed the threshold, I had NOT. I dove, head-first and with abandon, into the fountain of youth (drink up, drink up!). THEN came two unfortunate mileposts. First, the start of the last month before my own Bloomsday. Second, the impending start of the new academic year (oh woe!). And with them, an urge to commemorate almost as irresistible as the urge to procrastinate. Inevitably, I stepped into my own TARDIS and took off.

The rules: I would not repeat Mr. K (although right away I screwed up with Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, and it also, annoyingly, means I can’t use Claude Lévi-Strauss’s Le cru et le cuit). While literature-centered, I am after all a cultural historian, and would include music, film, and other types of production. I would focus on single poems or articles as much as on longer works. And, this being majorly about procrastination, I vowed to really read, hear, or view whatever I included, a requirement that benefited Jeff Bezos’s ever-swelling pockets but also sent me on more than one physical trip to the University Library’s deepest depths. Maybe embarrassed about my copycat quest, but also wanting to avoid never-ending comment threads, I made the odd choice to sidestep Facebook and “secretly” post on LinkedIn, where my few “Connections” are mostly limited to literature/culture colleagues and a number of former students whom at one point or another I guided in the pleasures of reading (what I hope they’ll most remember me for). Additionally, LinkedIn does not preserve a posting history (I think), so after a few weeks there would remain no evidence that, like George in Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man (of, you guessed it, 1964), I just get “steadily sillier and sillier.” Judging by both the number of views (I fancy having brought a welcome literary moment or two to people in their oppressive offices) and the merciful comment silence (which gives me the illusion that I did not, in fact, “share” my treasure), this might have been the right forum.

I still have over two weeks left, but this is what I’ve (un)covered so far: It was EASY to start with two of my favorite books by two of my favorite poets: Frank O’Hara’s Lunch Poems and Philip Larkin’s Whitsun Weddings (both anniversaries having been marked by the press, for example here and here). Same with Charlie. I then reread the first edition Saul Bellow’s Herzog, aided by Roger Cohen’s actually poignant New York Times homage review. Next came Isherwood, also in the paper version that originally sold for $4.00 (!). I newly discovered Leonard Cohen’s unfathomably sad Flowers for Hitler. And John Lennon’s delectably nonsensical In His Own Write (download here)–beware all you spelling purists because, as he himself tells us, “I was never any good at spelling, all me life. . . All I’m trying to do is tell a story, and what the words is spelt like is irrelevant really.” My latest textual recovery was Agatha Christie’s A Caribbean Mystery, which I truly can’t remember if I’d read before (I went through all her Biblioteca de Oro Spanish translations when I was a pre-teen–they had the best covers by Tom Adams).

I now read the whole thing looking for a quote that would inspire me and found NONE. It’s not just that the novel is so dialogue-based it’s hard to find any narration (and thus introspection); the British-shallow characters hardly ever say anything vaguely interesting. I ended up quoting Dictionary.com, which took one of the novel’s lines to illustrate usage of a word-of-the-day, “shilly-shally.” But of course, ALL OF THAT is what Christie is all about, and I still had oodles of fun!

It does not escape me that Christie is the only woman writer on this list, which must be remedied (is this why Mr. V keeps insisting that I am, deep inside, a man?). But then again, it’s a reality of the publishing world…

I have yet to read Chinua Achebe’s Arrow of God. Martin Luther King’s Why We Can’t Wait. ETCETERA!!! I’ve been shirking Spanish texts so far (like Pablo Neruda’s Memorial de Isla Negra [Isla Negra: A Notebook]), perhaps for the same reason I’ve never been able to say “I love you” to anyone in Spanish. Only one share to date isn’t poetry or fiction: Susan Sontag’s (the other woman’s!) groundbreaking critical essay “Notes on Camp,” so influential at a certain moment in my scholarly–and personal–development. And also still only one song, The Animals’ supergroovy “House of the Rising Sun” (but other great ones are definitely in store, in part courtesy of Mr. K himself, who sent me some). I haven’t even started with film (but first in line is Dr. Strangelove). Or given any thought to other arts! Like I say, two-and-a-half weeks to Bloomsday.

Surprisingly, and perhaps because I’ve been concentrating so much on literature, the experiment has only yet given me an oblique and indirect view–O’Hara: “A / Negro stands in a doorway with a / toothpick, languorously agitating”–of the time into which I was born. This post-Kennedy world of Vietnam; and Muhammed Ali; and a newly “triumphant” Cuban revolution (and people all over who still thought, rightly or wrongly, in terms of revolution); and the threat of nuclear war; and Bob Dylan; and dreams of reaching the moon; and what we thought was the winning battle for Civil Rights; and a feminism (Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique came out on paperback that year) that was still about complete equality and liberation, and not only about leaning in or back or around the purportedly primal and prime female desire for motherhood. And the friggin’ Beatles (since I always take sides, I’m for the Rolling Stones).

More evident has been that, in 1964 as across history, artists were drawn to “universals.” Love gained and lost. Isolation, loneliness. Life. Opportunity and coming-of-age. Aging. Death (and murder!). Divinity, or the lack thereof. Place (the city of New York prominent in this sample).

Those are, of course, suggestive observations (not sure they make the grade as “insights”). But the experiment is about something else that I, who make my living explaining things clearly, am not sure I can explain clearly.

But maybe this does: my favorite replevin of the past couple of weeks. I discovered James Merrill (together with Larkin, Wright, Heaney, and Levine) in an undergrad course at Johns Hopkins, and was immediately enraptured by The Changing Light at Sandover. As a graduate student, I was enamored when Merrill read at Harvard’s Boylston Hall and signed my well-worn copies of all his books (and everyone who knows me will attest to the fact that, as a rule, poetry readings make me want to puke). And now, my Google search surprisingly returned me to all that through his poem “Days of 1964” (since I’m quoting it in its entirety, I will encourage you to buy the book):

Houses, an embassy, the hospital.

Our neighborhood sun-cured if trembling still

In pools of the night’s rain . . .

Across the street that led to the center of town

A steep hill kept one company part way

Or could be climbed in twenty minutes

For some literally breathtaking views,

Framed by umbrella pines, of city and sea.

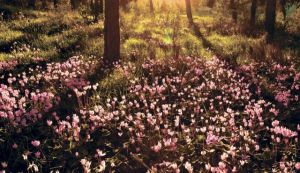

Underfoot, cyclamen, autumn crocus grew

Spangled as with fine sweat among the relics

Of good times had by all. If not Olympus,

An out-of-earshot, year-round hillside revel.I brought home flowers from my climbs.

Kyria Kleo who cleans for us

Put them in water, sighing Virgin, Virgin.

Her legs hurt. She wore brown, was fat, past fifty,

And looked like a Palmyra matron

Copied in lard and horsehair. How she loved

You, me, loved us all, the bird, the cat!

I think now she was love. She sighed and glistened

All day with it, or pain, or both.

(We did not notably communicate.)

She lived nearby with her pious mother

And wastrel son. She called me her real son.I paid her generously, I dare say.

Love makes one generous. Look at us. We’d known

Each other so briefly that instead of sleeping

We lay whole nights, open, in the lamplight,

And gazed, or traded stories.One hour comes back—you gasping in my arms

With love, or laughter, or both,

I having just remembered and told you

What I’d looked up to see on my way downtown at noon:poor old Kleo, her aching legs,

Trudging into the pines. I called.

Called three times before she turned.

Above a tight, skyblue sweater, her face

Was painted. Yes. Her face was painted

Clown-white, white of the moon by daylight,

Lidded with pearl, mouth a poinsettia leaf.

Eat me, pay me—the erotic mask

Worn the world over by illusion

To weddings of itself and simple need.Startled mute, we had stared—was love illusion?—

And gone our ways. Next, I was crossing a square

In which a moveable outdoor market’s

Vegetables, chickens, pottery kept materializing

Through a dream-press of hagglers each at heart

Leery lest he be taken, plucked,

The bird, the flower of that November mildness,

Self lost up soft clay paths, or found, foothold,

Where the bud throbs awake

The better to be nipped, self on its knees in mud—

Here I stopped cold, for both our sakes;And calmer on my way home bought us fruit.

Forgive me if you read this. (And may Kyria Kleo,

Should someone ever put it into Greek

And read it aloud to her, forgive me, too.)

I had gone so long without loving,

I hardly knew what I was thinking.Where I hid my face, your touch, quick, merciful,

Blindfolded me. A god breathed from my lips.

If that was illusion I wanted it to last long;

To dwell, for its daily pittance, with us there,

Cleaning and watering, sighing with love or pain.

I hoped it would climb when it needed to the heights

Even of degradation as I for one

Seemed, those days, to be always climbingInto a world of wild

Flowers, feasting, tears— or was I falling, legs

Buckling, heights, depths,

Into a pool of each night’s rain?

But you were everywhere beside me, masked,

As who was not, in laughter, pain, and love.

I would sound trite and maudlin if I tried to explain everything I experienced reading this. It is, first of all, seductive. Recently I called someone a verbert: someone who demands to be wooed with words, as much as images or actions. I think I am one too, and Merrill is my boyfriend forever.

Naturally, there’s all that makes a master’s poem a master poem. How Merrill plays with verse and stanza, and the way that rhythm follows the poetic voice’s epiphany (Ernest Hilbert compares the poem’s “oscillating rhythms” to “a waltz,” and Merrill to “a conductor [who] will alter the smallest element of a piece of music to great affect when performed”). The circularity of the form (those pools of night’s rain at beginning and end) that mirrors the conceptual circularity in which Kyria Kleo and the lover end up merging into a dual totality, as do the heights (of hills, of love) and the depths (of sinking in mud, of degradation). The way in which the last verse’s laughter, pain, and love literally fuse feelings separately ascribed to discrete people and experiences earlier on into a single figure masked, as who was not (was not “masked,” “everywhere beside me,” or “falling”?). Someone we know, from just one line (“forgive me if you read this”), is gone (the way of Kyria Kleo)–and who both is, and isn’t, David. The BRILLIANT imagery: you can see Merrill links the flowers he picks to the poinsettia-leaf lips of Kyria Kleo (thus they must somehow represent what she represents). So let me also tell you, for example, that both cyclamen and autumn crocus (also known as naked lady) are low-growing flowers he would have picked right off the dirt (underfoot, offering foothold). Cyclamen’s name comes from the Greek kýklos “circle,” and autumn crocus is as beautiful as it is deadly poisonous: Greek slaves killed themselves by eating it. Could Merrill have chosen better metaphors?

There are also the references, from the modern Athens where Merrill had just bought a house, to ancient Greece. The connection is concretized in Kyria Kleo as the Palmyra-matron copy (an “impostor” of Roman virtue like Zenobia), who, through this iconography, metonymically becomes one side of the duplicitous tragicomic mask (the other is the lover). The Greek connection intertextually extends to Constantin Cavafy, whose own “Days of” poems (“Days of 1896,” “Days of 1901,” “Days of 1903,” “Days of 1908,” and “Days of 1909, ’10, and ’11”) Merrill not only evoked (in form and content) but translated:

That year he found himself without a job.

Accordingly he lived by playing cards

and backgammon, and the occasional loan.A position had been offered in a small

stationer’s, at three pounds a month. But he

turned it down unhesitatingly.

It wouldn’t do. That was no wage at all

for a sufficiently literate young man of twenty-five.Two or three shillings a day, won hit or miss―

what could cards and backgammon earn the boy

at his kind of working class café,

however quick his play, however slow his picked

opponents? Worst of all, though, were the loans―

rarely a whole crown, usually half;

sometimes he had to settle for a shilling.But sometimes for a week or more, set free

from the ghastliness of staying up all night,

he’d cool off with a swim, by morning light.His clothes by then were in a dreadful state.

He had the one same suit to wear, the one

of much discolored cinnamon.Ah days of summer, days of nineteen-eight,

excluded from your vision, tastefully,

was that cinnamon-discolored suit.Your vision preserved him in the very act of

casting it off, throwing it all behind him,

the unfit clothes, the mended underclothing.

Naked he stood, impeccably fair, a marvel―

his hair uncombed, uplifted, his limbs tanned lightly

from those mornings naked at the baths, and at the seaside.(“Days of 1908,” Merrill translation)

An inveigling homoerotic poem about the devastating beauty of “a sufficiently literate young man of twenty-five” whose depths of degradation were also the heights of love. (Oy, Mr. V, if I am indeed a man, it’s also clear that I’m gay. And, aspirationally, the son of Charles E. Merrill.)

And so on, and so on. If such things were allowed (alas, they’re not!), I could spend an entire semester with a group of students just picking this poem apart. But that is simply (simply?) the experience of reading a phenomenal piece of literature. The 1964 experiment, however, brought it to me in a unique way: it is mine, because the year was mine, because I found it with my TARDIS, and because it is now part of a work I composed with Merrill and O’Hara, and Larkin and Cohen, and Dahl and Lennon, and Isherwood and Bellow, interpreted by Sontag, to the tune of The Animals.

Bloomsday, the yearly celebration of James Joyce’s Ulysses, is about a million people repeating a single experience, yet making it their own. So was, by the way, the Hull-to-King’s Cross journey with which Larkin fans celebrated Whitsun Weddings’s fiftieth year in 2014, two days before Whitsun. This experiment is my own such journey. If every Doomsday must become a Bloomsday, and every Bloomsday needs its Odyssey, I’m halfway to Ithaca. And it’s superduper fun!

Just read a new “Book of 1964” and hated it. Which isn’t quite how this was supposed to go. (John Berryman, *77 Dream Songs* – National Book Award poetry finalist, 1965.) http://www.poets.org/poetsorg/book/dream-songs

LikeLike

A poet’s letter, 1964. “Well, nevermind. I think language is beautiful. I even think insanity is beautiful (surely the root of language), except that it is painful. Language is verbalizing the non-verbal. (That’s what makes it so complicated.) Hoding hands is better than saying ‘I love you.’ When Kayo shoots squirrels it is better than saying ‘I hate you’. . . that’s part of language. Language in action is symbolic. Language in words is, too, but it is more difficult to follow.” Anne Sexton, to Anne Clark. 3 July. http://www.lindagraysexton.com/book_portrait.html

LikeLike

Jorge Luis Borges, “1964” (El otro, el mismo, 1964). Online transcription of Spanish original and English translation: http://www.interpals.net/note.php?nid=39768

LikeLike

Another book of ’64. Hemingway’s posthumous Paris memoir, A Moveable Feast. The kid and the cat: “It was wrong to take a baby to a cafe in the winter though; even a baby that never cried and watched everything that happened and was never bored. There were no baby-sitters then and Bumby would stay happy in his tall cage bed with his big, loving cat named F. Puss. There were people who said that it was dangerous. . . F. Puss lay beside Bumby in the tall cage bed and watched the door with his big yellow eyes, and would let no one come near him when we were out. . . There was no need for baby-sitters. F. Puss was the baby-sitter.” http://charlyawad.com/images/books/A%20Moveable%20Feast%20-%20Ernest%20Hemingway.pdf

LikeLike